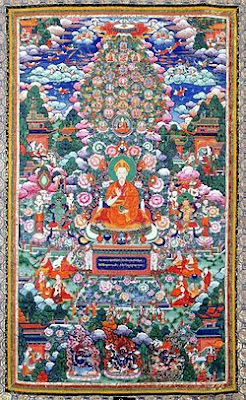

Thangka are paintings of sacred, ritualistic and ceremonial

subjects on Buddhism hung up in temples, monasteries and private chapels. Such

painting are meant for meditation as they are the manifestation of the deity. The Buddhists have rituals galore.

The Tibetan painting can be examined at two distinct levels:

its visual vividness and portrayal of Bhuddhism pictorially. These painting symbolizes

the real points of Buddhism , its endless variety of socio-religious themes and

attempts to express the mystical world which is very complicated.

Thangka are paintings or, occasionally embroidered pictures,

usually called “banners”. They first came into use about the tenth century.

Before that time painting was mostly confined to frescoes on the walls of the temples

or monasteries or in caves. Most of the Thangka we see in the Occident probably

date from the 17th century to the 19th century.

These Thangka are hung in the temples and at the family

alters in homes. They are also carried by the Lamas in religious processions. This

particular school of art expresses the mode of life of the Tibetans in an

unique style with total honesty, sincerity and beauty. The Thangka painting portrays

how artistic and sensitive the Tibetans are. In Tibetan language Thangka means

something that can be rolled. These painting are done on cloths and rolled. The

term Thangka is derived from two words: Than and ska. These two words mean

realistic form and personification of the avtar (reincarnation).

At the initial phase only the painting related to life of

Lord Buddha used to be given in the Thangka painting but gradually included

portrayal of different other subjects related to Buddhism. Often they depict

stories which the Lamas use to illustrate their sermons.

The Thangka are usually painted on canvas, sometimes on

paper, but rarely on silk. The canvas is sized with one part glue to seven

parts white chalk mixed with tepid water. Then it is stretched on a frame to

dry. It is rubbed with a smooth stone, sprinkled lightly with water, and again

left to dry. After studying under the guidance of a Lama artist, the student

monk prepares the canvas and puts the outline on the canvas from a transfer of

dotted lines. Then the colors are made ready. At first the colors were made

from minerals and vegetables. The blue and green mineral colors are ground from

mineral rocks found near Lhasa. The Yellow comes from the province of Khams.

The reds are made of oxide, of mercury, and the vermilions is imported from

India and China. Gold is brought from Nepal. The vegetable colors are: black,

made from soot of pine wood; indigo, from the indigo plant from India; yellow,

from a flower growing in the vicinity of Lhasa, the utpala flower; lac, from the lac insect of India and Bhutan.

The minerals are

ground, and then mixed in various proportions with water, glue, chalk, and lac

or alum to give the different degrees of consistency and shading. The plants

and vegetables are boiled before being prepared with the required amount of

glue.

The brushes used are pine twigs hollowed at one end, into which

goat or rabbit hairs are inserted to the required thickness. A compass made of

two pieces of split bamboo is needed also in order to get the correct

measurements of the figures on the canvas, according to the canonical rules.

Usually the student does the work up to this point. The lama artist continues

from there. He paints in the landscapes and figures. The important details,

such as the faces of the deities and the inscriptions, are executed on

auspicious days decided on by the astrologer Lamas. When the painting is

finished, it is mounted with a silk or brocade border, and usually a thin silk

dust-curtain is put over it. Around the painting there should be a narrow red

border, then a narrow yellow boarder, and last the wide blue mounting, in

proportion to the size of the canvas. When the original mountings wear out, they

are sometimes replaced by other colors. Usually there is a flat stick to which

the banner is attached at the top. At the bottom there is a roller, sometimes

with ornamental ends, to weight the banner and keep it straight and firm. Red,

yellow, and blue are the three primal colors used in mounting the banners.

When the banner is

finished, it is consecrated by a high lama. Occasionally one finds on the back

the print of the hand or of the foot of a Living Buddha. The subjects and

composition are often very striking and vivid, and they produce spectacular

effects when seen by the light of the flickering butter lamps in the dim

interiors of the temples.

It is necessary to go to the symbolic perception of thangka

painting to understand different aspect of the Tibetan Buddhist. The followers of

Buddha adopted the system of painting as the best method to propagate the religious

concept of Buddhism as the rolled thagka were much easier to carry then the

idols. In fact they used these painted rolls as a substitute for idols to popularize

the philosophy of life and practical teachings of Lord Buddha. The Thangka

painting acted as substituted form of books on Buddhism also. Even the kings

following Buddhism laid more emphasis on these paintings then books that led to

the popularity of Buddhism all over Tibet. These painting played a prominent

role in spreading Buddhism to different countries including Japan, China, Java,

Sumatra, Burma and Sri Lanka.

According to famous writer Tucci the thangka represents the

symbolic as well as imaginary facts through colors. By the medium of thangka

the Buddhism finds its depiction. Tucci, an Italian expert on Tibet says -

“This particular painting is mirror of actual Tibetan life. It reflects the

philosophy and religious precepts of Buddhism as a whole. “

The Dalai Lama however believes the thangka painting shows

the inner eye and very high depth of knowledge of the Tibetan Lamas regarding

philosophy, religion and practicality vis-a-vis the Buddhism. Certainly, this

school of art, the Dalai lama says, gives joy to many, posses curiosity among

several people and offers new inspiration to the people to wake up to new awakening.